ERNEST LAWSON ON THE EVENING OF LIFE

Miguel de Unamuno, the great Spanish writer, poet, and philosopher, who flourished a century ago, did not mince words. He said that Spain’s great epic tale, Don Quixote, did not belong to its author, Miguel de Cervantes, but to the people of Spain. In his essay “On the Reading and Interpretation of Don Quixote,” Unamuno wrote, “If Cervantes was Don Quixote’s father, his mother was the country and people of which Cervantes was part. Cervantes was merely the instrument by which sixteenth-century Spain gave birth to Don Quixote.” In another passage Unamuno asks, “Since when is the author of a book the person to understand it best?”[1]

I believe that Unamuno’s question also applies to our great American epic, Moby-Dick, or The Whale, written by Herman Melville. Since the book was rediscovered by critics and reviewers after World War I, they have found (or, sometimes, thought they found) much more in that great tale than its author would have deemed possible. The significance and meaning of a work of art continue to unfold as successive generations encounter and are touched by it. I shall now attempt to apply this concept, not to a great national epic, but to a small painting by a Canadian and American artist, Ernest Lawson.

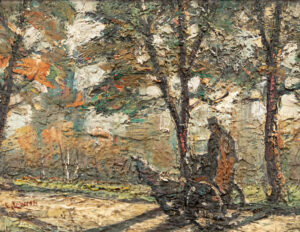

Lawson (1873-1939) was known primarily as an impressionist or post-impressionist painter of landscapes. He is an artist of the Ashcan School, also known as “The Eight.” He did not have an easy life. Much of his work presented scenes in the northern portion of Manhattan, and the setting of this untitled work appears to be New York City’s Central Park. Lawson was less drawn to gritty urban realism than some of the other members of his school. Yet there is an element of it in this painting. In a wealthy area of a rich city, his subject is a worker riding in a cart, which is being pulled by a donkey. Most likely the man is employed in maintenance of the park; or he could be a peddler. In any event he is not a member of the city’s elite.

The painting is unusual among Lawson’s works in at least three ways. The first is its size, eight by ten inches. I cannot recall having seen another Lawson landscape that is so small. I would love to know why he chose a diminutive format for this one. Sometimes a small oil is a study for a larger one. If there is a larger version, I have not been able to find it. And to me everything in this work, including the signature, says that this is a finished painting.

Lawson rarely has a single figure so prominently featured in a landscape: the worker is nearly as tall as half of the vertical measurement of the scene. The vast majority of people in Lawson’s landscapes are smaller, compared to the size of the canvas, and they are usually not alone. His painting The Towpath, which is often reproduced, also has one workman and a horse, but they are much less prominent in that larger work.

Another distinguishing feature is the angle of the sun: there are very few of Lawson’s landscapes where the shadows make the setting sun such a notable, though unseen, influence. His focus is usually on the scenery, and the lighting is less evident to the viewer. Yet in this Central Park painting, we are highly aware of the effects of the sun. Lawson uses them to produce the focal point of the painting, which is not near the center. At lower left, next to the signature, it is the empty space on the road just ahead of the laboring donkey.

These three unusual features, the diminutive presentation, the prominence of the man and his beast, and the powerful use of the nearly horizontal sunlight, combine to make me believe that Lawson has a message for us in this little bit of oil. How conscious he was of it, we can hardly say. He may have been highly aware, yet not inspired to articulate his message in words. But if Unamuno is right about Don Quixote, may we not be pardoned for trying to sound the depths of Lawson’s masterful depiction of this moment?

Some things are clear: it is late in the day; it is late in the year; the donkey is straining to get to his stable; and the man’s posture is less than erect. The light is still bright; the fall is still beautiful; but the night and the winter are coming soon. Yet the painting is not the work of an old man, and the vigor, even the daring, of the brushwork, is lively and captivating.

Some oil paintings have smooth surfaces, and their texture is a secondary matter. Not here: the heavily-impastoed panel resembles a relief map. Somehow it seems rough, chaotic, and yet fluid, all at the same time. At close range some of the details, like the backs of the man and the donkey, seem too bold or even incoherent, but at a proper distance they fit together beautifully.[2]

Framing is another vital component of visual art. To me, the elaborate three-dimensional elements in the frame blend nicely with the surface of the painting. Originally the gilded frame would have been much brighter, perhaps shockingly so, compared to its present state. Yet, when the painting was meticulously cleaned, the restorer chose not to regild the frame. I think this adds emphasis to the contents of the work: this message is coming to us from a time already distant from our own.

Even if Lawson had live models for his man and his donkey, which I doubt, the rapidly changing sunlight would have given him only a few minutes to capture this scene. I think it more likely that he saw something that fascinated him, and he recreated it in this picture. It might be more accurate to title this blog “Ernest Lawson and the Late Afternoon of Life,” but I think the artist was intent on communicating the beauty of what is, when the time and the season are late, gently reminding us of the cold and the darkness that are coming. We need to get to our stable while we can . . . .

A hard message, perhaps, but Lawson communicates it so beautifully that we should take hope. A collector who owned this painting for decades remained optimistic about humanity, in spite of our dreadful shortcomings, because he was so intensely aware of the inspired works that God has given us, often through the gifted minds and hands of troubled artists like Ernest Lawson.

[1] Unamuno felt so strongly about this that he expanded the essay into a book, Our Lord Don Quixote.

[2] The ultimate example of this technique I have long thought to be the wine glass on the table at the forefront of Renoir’s Le Déjeuner des Canotiers [Luncheon of the Boating Party] at The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. Close up, it’s a blur of abstract paint; step back, and it becomes a luminous jewel. Lawson’s small painting has proportionately more of this effect than Renoir’s large one. But Renoir’s use of it is supreme.

© 2022 Philip Rosenbaum

“Central Park” by Ernest Lawson (signed, lower left), oil on panel, 8″ x 10″, private collection, used by permission.

Photo credits: Rob Coulter